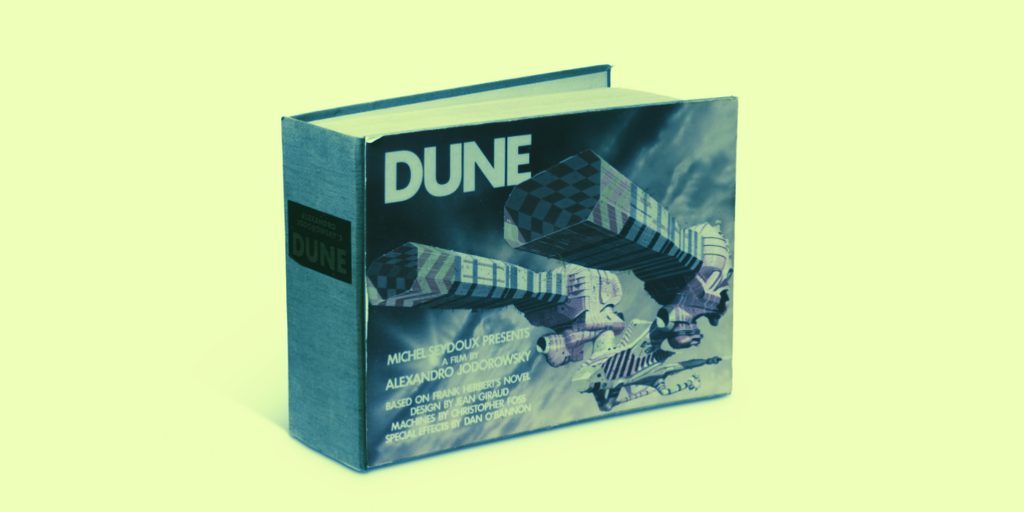

This DAO ‘Bought’ Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Dune Bible—But It Doesn’t Own It Yet

In brief

Spice DAO raised $11.8 million to finalize the purchase of the famed “Dune Bible.”

The DAO’s co-founder put up $2 million of his own funds to win the auction.

Here’s a quick conundrum. Does the person paying the mortgage own the house, or is it really the property of the bank? Here’s another one: Do viewers own the rights to digital movies they purchase online?

And, finally, who really owns filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky’s “Dune Bible”? Is it the DAO (decentralized autonomous organization) that raised $750,000 to bid on it at Christie’s auction house, or the DAO’s co-founder who used his own funds to purchase it separately—and then spearheaded a fundraising drive for other contributors to buy it back from him?

That’s the curious question being raised this week by Spice DAO (formerly DuneDAO), the latest decentralized community formed to purchase real-world items—just as ConstitutionDAO attempted for a copy of the U.S. Constitution and Krause House aims to do for an NBA team.

DuneDAO was co-founded by Soban Saqib, who goes by “Soby,” along with a friend to raise money and bid on storyboards for the planned (but never filmed) 1970s film adaptation of Frank Herbert’s novel “Dune.” Though the $750,000 in Ethereum they raised via community funding site Juicebox was far more than Christie’s estimated value of €25,000-35,000, it was far below what was needed to win the auction last week. More than that, it was in the wrong type of currency—the auction’s seller wasn’t accepting Ethereum.

Watching the drama unfold, Soby put down his own cash—€2,660,000 ($3,010,750), not including fees—to avoid the fate of the unsuccessful ConstitutionDAO, which raised $45 million but decided the auction fees and storage costs of the centuries-old constitution would be too costly.

“No one wants to fail, no one wants to raise all this money and not win, so I did it,” he told Decrypt. Soby added he was a little worried about bidding that much money but knew the community would support him.

Ever since, he says he’s been looking for a way to transfer the Dune Bible to the DAO, the idea being for it to effectively reimburse him. Soby told Decrypt he’s unsure how much his own investment in the manuscript will total when all is said and done; the cash bid has complicated things.

“No one wants to fail, no one wants to raise all this money and not win, so I did it.”

Aside from ownership issues, according to Soby, the DAO hasn’t decided where the physical book will ultimately live or who will have access. For now, it’s in a holding pattern with the auction house before ownership is transferred. One idea being floated is to display the Dune Bible in a public place. Presumably, the final decision will be made by all community members via $SPICE—the token that contributors received in exchange for their ETH; the plan is to make it a governance token that gives holders a vote on investment decisions.

The starting point for getting the Dune Bible out of Soby’s hands was a new fundraising effort, this time under the moniker of SpiceDAO. (Soby intimated there were copyright concerns over titling the DAO after Dune, but spice is a reference to the novels and the group’s token.) DAO member “Charlottefang” announced on Discord that the group has raised $11.8 million in ETH and fiat (which includes Soby’s payment at auction)—a portion of which will be used to settle the auction with Christie’s and reimburse Soby, with the rest to be used for future projects.

According to a Monday post from Soby, those projects include “a goal of funding an animated film or series and other creative projects, directed by community decisions, inspired by the intent and vision of Jodorowsky’s Dune.” Assuming, of course, others in the DAO are inspired by Soby’s vision.

Although DuneDAO has been able to rebrand quickly and raise cash, the confusion it has generated is a reminder of how the idealism of DAOs can often hit a wall with the reality of ownership logistics, physical item storage, and even just making a bid.

But Soby is unfazed: “People like us never had a seat at the table to decide what was culturally relevant. And now we do.”